Our Holistic Approach

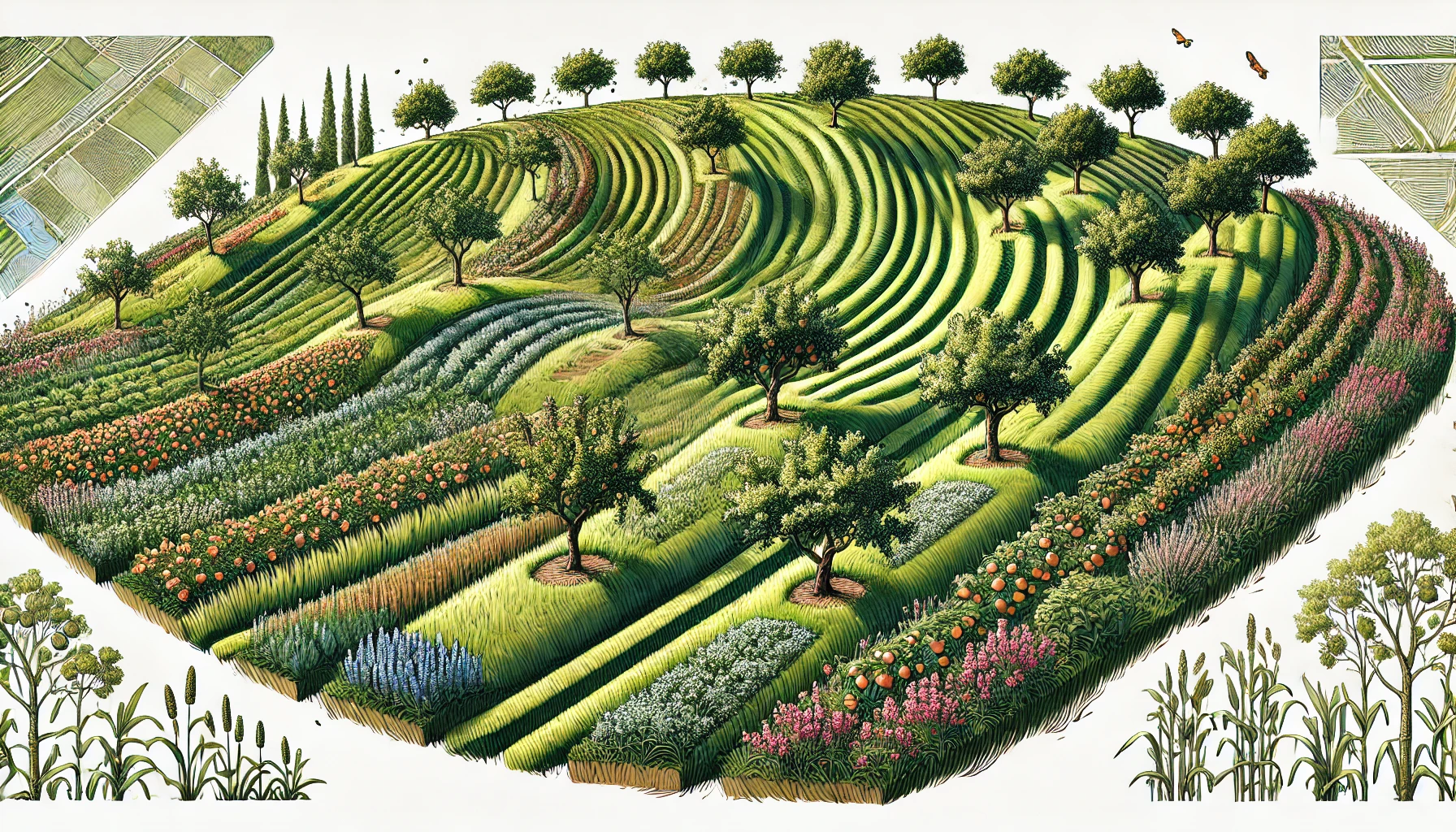

A principles-based approach to ecological landscaping seeks to balance human aesthetics and convenience with the inherent wisdom and resilience of natural processes. By blending the desire for low-maintenance beauty with the principles that guide healthy ecosystems, landscape designers can foster vibrant, functional outdoor spaces that are as beneficial for people as they are for local wildlife.

- Assess and Build Soil Life: Understand existing soil conditions, including pH, texture, and organic matter content. Amend as needed with natural materials (e.g., compost, leaf mold) to improve soil structure and microbial life.

- Minimize Disturbance: Reduce tilling, compaction, and chemical use to help soils maintain their natural structure and biodiversity.

- Mulch and Groundcover: Use mulch layers or living groundcovers to protect soil, moderate moisture levels, and reduce weed competition.

Why it matters: Healthy soil contains a complex web of organisms that break down organic matter, cycle nutrients, and support vigorous plant growth—all of which lowers long-term maintenance.

- Match Plants to Site Conditions: Factors like sun exposure, drainage, soil acidity, and moisture levels should guide plant selection. Proper matching reduces watering, fertilizing, and pest control down the road.

- Use Regionally Adapted Species: Emphasize native plants or well-adapted non-natives that thrive in local conditions. They are more likely to be pest-resistant and less dependent on human intervention.

- Diverse Plant Selections: Group plants by similar needs (e.g., “hydrozones” for water requirements or “shade communities”) to streamline irrigation and care.

Why it matters: When plants naturally suit the site, they can flourish with minimal inputs, growing stronger and healthier while requiring less active maintenance.

- Pollinator Support: Incorporate flowering plants that bloom at different times, including native wildflowers, shrubs, and trees. Provide nesting and overwintering habitats for beneficial insects (like leaving some leaf litter and stems).

- Wildlife Corridors: If possible, link your landscape to nearby green spaces or natural areas so that animals, insects, and birds can move between habitats.

- Avoid Monocultures: Planting large areas with a single species can invite pest or disease outbreaks. Diversity builds resilience.

Why it matters: Biodiverse landscapes tend to be more stable and self-regulating, cutting down on pest control needs and labor over time.

- Natural Pest Management: Encourage beneficial insects (ladybugs, lacewings) and birds by planting “habitat hubs” and using plants that support them, rather than using broad-spectrum pesticides.

- Fertility Through Organics: Use compost and organic fertilizers instead of synthetics. This feeds soil life and avoids the detrimental side effects of chemical runoff.

- Tolerate Minor Imperfections: Embrace a less manicured aesthetic where some leaf damage or volunteer plants (weeds) are acceptable, unless they threaten landscape integrity.

Why it matters: Chemical reductions protect pollinators, waterways, and soil organisms, and help maintain a balanced ecosystem that naturally regulates pests and diseases.

- Group by Maintenance Needs: Cluster plant communities that share watering, pruning, or soil requirements. This reduces the time spent on separate tasks scattered around the site.

- Select Long-Lived Species: Choose robust perennials, shrubs, and trees that won’t require constant replanting or heavy pruning.

- Use Groundcovers and Mulch: These minimize weeds and regulate soil temperature and moisture, cutting down on weeding and watering.

Why it matters: Good upfront design means that, as plantings mature, nature does much of the work—resulting in a landscape that’s attractive without being labor-intensive.

- Observe and Iterate: Periodically assess plant health, soil moisture, pest activity, and changes in microclimates. Adjust as needed—removing or replacing underperforming plants, refining mulching methods, or adjusting watering schedules.

- Allow for Change Over Time: Understand that ecological landscapes evolve. As trees mature or new seedlings appear, plan for transitions and successions.

- Keep Records: Track plant performance, pest outbreaks, and maintenance tasks to guide future decisions and improve design efficiency.

Why it matters: Natural processes are dynamic; an adaptive management style allows you to steer your ecosystem smoothly through change while respecting its inherent rhythms.

Putting It All Together

A truly ecological landscape weaves soil health, plant diversity, and wildlife habitat into an aesthetically pleasing design that echoes nature’s processes. By focusing on matching plants to the site’s conditions, encouraging biodiversity, minimizing chemical inputs, and embracing an adaptive approach, designers and homeowners can enjoy landscapes that are both visually engaging and functionally resilient.

This blend of mindful planning, ecological principles, and ease-of-care creates outdoor spaces that sustain themselves—and the life around them—while providing year-round beauty and enjoyment with minimal ongoing labor.

Inspiration

Inspiration is the Font of Youth.

Permaculture

Core Idea:

Developed by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren, Permaculture aims to create self-sustaining, productive ecosystems modeled after natural patterns. At its heart is a systems-thinking approach that integrates water management, soil health, plant communities, and human needs into one regenerative design.

Applied Design Philosophy:

- Zoning and Layering: Gardens are laid out in “zones” (from intensive near the house to less-managed at the perimeter) and stacked vertically with multiple “layers” (e.g., canopy, understory, herbaceous).

- Diverse, Functional Plantings: Emphasis on polycultures (guilds) that fulfill multiple roles—providing yields, fixing nitrogen, attracting pollinators, or repelling pests.

- Closed Loops: Composting, rainwater harvesting, and on-site resource cycling minimize waste and reduce external inputs, making landscapes more self-reliant over time.

Roy Diblik’s Know Maintenance Garden

Core Idea:

Roy Diblik’s “Know Maintenance” philosophy centers on understanding plants’ growth habits, life cycles, and companionships to reduce upkeep over the long run. By grouping compatible species that thrive in similar conditions, gardeners can create dynamic yet relatively low-maintenance plant communities.

Applied Design Philosophy:

- Plant Communities by Habit: Diblik’s approach encourages using compatible plant groupings (e.g., a matrix of grasses under interspersed perennials) to crowd out weeds and streamline care.

- Seasonal Rhythms Over Quick Fixes: Rather than frequent, reactionary tasks, the Know Maintenance approach looks at each garden’s timeline—pruning, dividing, or cutting back at optimal seasonal windows.

- Observation & Adaptation: The gardener actively observes plant performance, adjusting combinations or timing of tasks as plants mature and community dynamics shift.

Planting in a Post-Wild World

Core Idea:

Developed by Thomas Rainer and Claudia West, “Planting in a Post-Wild World” recognizes that truly untouched wild landscapes are increasingly rare. The authors advocate for designed plant communities that mimic wild ecosystems’ layered and interwoven structures, yet accommodate human and urban constraints.

Applied Design Philosophy:

- Layered Plant Communities: Different “strata” of plants—groundcovers, seasonal accents, structural layers—overlap to fill ecological niches and reduce bare soil (and thus weeds).

- Inspired by Nature, Shaped by People: While derived from natural plant patterns, the resulting gardens are thoughtfully orchestrated for modern spaces—whether in cities, suburbs, or public parks.

- Resilient, Adaptive Planting: By mixing grasses, perennials, and shrubs that share ecological compatibilities, these designs handle environmental stress while supporting biodiversity.

The Living Landscape

The Living Landscape

Core Idea:

Authored by Rick Darke and Doug Tallamy, “The Living Landscape” underscores the importance of designing landscapes that function as wildlife habitats and ecological corridors. This means carefully selecting plants that support pollinators, birds, and local fauna while offering aesthetic and practical benefits to people.

Applied Design Philosophy:

- Native Plant Emphasis: Native species serve as the “backbone,” providing food, shelter, and nesting sites for insects, birds, and small mammals. Exotic but non-invasive plants can still have a place, but the ecological core rests on natives.

- Layered, Multi-Season Interest: A mosaic of groundcovers, understory shrubs, canopy trees, and meadows creates visual diversity year-round while sustaining wildlife.

- Functional Beauty: The aim is both visually compelling and ecologically rich—lawns are minimized or replaced by meadows or woodland gardens, and features like water sources or dense hedgerows become lifelines for wildlife.

Bringing It All Together

While each philosophy differs in emphasis—Permaculture’s system-based regeneration, Diblik’s practical grouping and scheduling, Post-Wild’s ecologically inspired design layers, and The Living Landscape’s wildlife focus—they converge on a single goal: creating landscapes that thrive with minimal intervention, enrich local ecosystems, and offer natural beauty. From home gardens to community green spaces, blending insights from all four can result in spaces that are both productive for people and supportive of the broader web of life.

Other Resources

Gertrude Jekyll (1843-1932)

Gertrude Jekyll’s gardening philosophy can be best described as "artful naturalism," deeply rooted in the integration of horticulture, ecology, and artistic expression. At its core, her approach emphasizes creating gardens that blend harmoniously with their surroundings, reflecting the subtle beauty and inherent structure of nature.

Key principles include:

Harmony and Cohesion:

Jekyll believed gardens should form a seamless connection with their architectural setting, creating a unified aesthetic experience.

Painterly Planting:

Drawing from her training as a painter, she arranged plants in color-coordinated drifts and layers, evoking a living, impressionistic painting.

Seasonal Succession:

She advocated for thoughtful planting that ensures year-round interest and evolving beauty through carefully chosen bloom sequences.

Naturalistic Forms and Textures:

Her designs prioritize informal, organic shapes over strict geometric lines, allowing nature’s innate beauty to shine.

Craftsmanship and Material Authenticity:

Jekyll emphasized using local materials and handcrafted elements, such as stone paths, fences, and gates, to enrich the garden’s character.

Today, her philosophy resonates strongly with contemporary ecological design: gardens as interconnected, evolving ecosystems that honor both aesthetics and ecological function. A pioneering landscape designer and prolific author, Ms. Jekyll has left us the gift of her wisdom and experience.

Originally published in 1899, Wood and Garden remains a poetic exploration of garden-making, blending horticultural wisdom with deep ecological intuition. Gertrude Jekyll’s thoughtful reflections still resonate strongly with contemporary gardeners who value natural beauty and harmony in their landscapes.

At its heart, the book promotes the principle of integrating garden spaces into their natural surroundings, emphasizing that gardens should reflect and extend the local environment rather than overpowering it. Translated into modern practice, this suggests choosing native plants and local materials to create a sense of belonging within a landscape, fostering biodiversity, ecological resilience, and a profound connection to place.

Jekyll further illustrates the importance of understanding seasonal rhythms. She encourages gardeners to appreciate and utilize natural cycles, creating gardens that delight in every season. Today, gardeners can embody this concept by planting diverse species that provide continual interest—early spring bulbs, summer perennials, vibrant autumn foliage, and structural winter elements. Such seasonality supports ecological functions, sustaining wildlife through changing conditions.

Another timeless aspect is her focus on layering and naturalistic planting schemes. She advocates informal yet intentional designs, combining trees, shrubs, and herbaceous perennials into lush, multi-layered arrangements. Modern ecological gardeners interpret this by designing diverse plant communities that mimic natural ecosystems, boosting ecological function, visual appeal, and habitat quality simultaneously.

Jekyll also champions the strategic use of woodland edges and transitions between cultivated spaces and wilder natural areas. In contemporary landscapes, these transitional zones—often known as “ecotones”—are biodiversity hotspots. Modern gardeners can employ shrubs, grasses, and perennials suited to woodland edges, enhancing habitat and softening boundaries between cultivated gardens and surrounding wildlands.

Finally, Wood and Garden emphasizes the value of observing and responding to natural conditions rather than imposing rigid designs. Today, this translates into a gardening ethic that listens to the land, choosing plants and techniques appropriate to local soil, climate, and ecology, thus reducing the need for excessive inputs like water, fertilizer, or chemicals.

In sum, Wood and Garden remains a meaningful guide for contemporary gardeners seeking ecological inspiration and wisdom. Gertrude Jekyll’s principles encourage thoughtful design that celebrates seasonality, biodiversity, and the inherent beauty of nature, providing timeless guidance for crafting landscapes of lasting ecological and aesthetic value.

A thoughtfully examination of the intimate connections between a home and its surrounding landscape. Though written over a century ago, the core concepts presented are remarkably adaptable to today's emphasis on ecological mindfulness, sustainability, and integrated outdoor living.

Jekyll’s foremost principle is the harmonious integration of house and garden. She argues that a garden should serve as an extension of the home itself, reflecting its style, character, and daily rhythms. Modern gardeners interpret this by choosing landscape materials, plants, and design elements that echo architectural themes, creating cohesive indoor-outdoor living spaces that are both beautiful and functional.

Another key concept is her encouragement of gardens that are both visually appealing and practically useful. Jekyll emphasizes gardens that provide sensory delight, seasonal interest, and practical value. Today, this means incorporating native species for pollinators, edible plants for food, and medicinal herbs into ornamental landscapes—transforming aesthetic gardens into spaces that nourish people, wildlife, and ecological resilience alike.

Jekyll also emphasizes the importance of carefully designed garden structures and pathways. Features like stone walkways, pergolas, trellises, gates, and seating areas guide movement and shape experiences. Contemporary adaptation includes using sustainably sourced or reclaimed materials, creating natural transitions between different garden areas, and promoting accessibility, all of which enhance a garden’s usability and ecological sensitivity.

Further, Home and Garden discusses the thoughtful use of color and texture, suggesting carefully curated planting schemes that evolve through seasons. Modern gardeners can embrace these ideas by using diverse native plants, perennials, grasses, shrubs, and trees to create vibrant, layered planting arrangements. Such diversity enriches wildlife habitats, provides continual visual interest, and aligns with modern ecological principles.

Lastly, Jekyll underscores the garden as a place of rest and renewal. Gardens, she suggests, should be personal retreats that nourish both body and soul. Today’s gardeners can realize this vision by designing outdoor spaces for quiet reflection, relaxation, and reconnection with nature—prioritizing comfort, tranquility, and sensory delight as core elements of sustainable, wellness-oriented garden design.

In essence, Gertrude Jekyll’s classic Home and Garden continues to offer invaluable inspiration for modern landscape design. By translating her timeless principles into contemporary practices, gardeners can create outdoor living spaces that are aesthetically pleasing, ecologically responsible, and deeply restorative—truly timeless in their harmony between home, nature, and human well-being.

First published in 1901, Wall and Water Gardens by Gertrude Jekyll remains an influential and practical guide to designing landscapes around walls, water features, and vertical gardening structures. Even more than a century later, its insights resonate deeply with modern gardeners who seek innovative, sustainable ways to enrich their outdoor spaces.

Central to Jekyll’s approach is the thoughtful integration of vertical structures into garden design. Walls, trellises, pergolas, and fences aren't simply barriers but vibrant canvases for greenery. Modern gardeners can adapt this idea by creating vertical gardens filled with native vines, edible climbers, or flowering plants, transforming structural elements into lush habitats that offer visual depth, wildlife shelter, and even harvestable produce.

Jekyll also emphasizes the powerful potential of walls as microclimates. Walls store heat, moderate temperature fluctuations, and provide protection from wind. Translating this to contemporary terms, gardeners can strategically plant tender perennials, fruits, herbs, or delicate native species alongside south-facing walls, extending their growing season and expanding plant diversity in the garden.

In exploring water gardens, Jekyll reveals water’s unique ability to create tranquil, reflective spaces that enhance biodiversity. Today’s gardeners can embrace her insights by incorporating small ponds, rain gardens, or naturalized water features into their landscapes. Such additions not only attract birds, amphibians, and beneficial insects, but also help manage stormwater, reduce flooding risks, and support local ecological balance.

Furthermore, Jekyll stresses the importance of careful plant selection based on environment. She highlights the necessity of choosing species suited to specific locations, whether dry stone walls, moist pond edges, or shady vertical plantings. This aligns beautifully with current ecological gardening principles that prioritize native or adapted plant choices, promoting gardens that are both resilient and low-maintenance.

Lastly, Wall and Water Gardens emphasizes that gardens should delight the senses and spirit, not merely the eye. Jekyll encourages gardeners to create sensory-rich spaces, integrating fragrance, color, sound, and texture. Today’s sustainable gardeners might fulfill this vision by incorporating aromatic herbs near seating areas, grasses that rustle in breezes, colorful blooms for pollinators, and textured foliage along pathways.

In short, Gertrude Jekyll’s classic work offers modern gardeners timeless strategies for creatively using walls and water to build vibrant, functional, and ecologically supportive landscapes. By applying her principles with contemporary ecological knowledge, we can design spaces that enrich our lives, enhance wildlife habitats, and harmonize beautifully with the natural environment.

Originally published in 1908, Children and Gardens by Gertrude Jekyll thoughtfully explores the meaningful connections between young people and the natural world. More than a century later, Jekyll’s principles remain deeply relevant, particularly in our contemporary efforts to inspire ecological awareness, hands-on learning, and stewardship among children.

Central to Jekyll’s approach is the idea that gardens should be designed as living classrooms, spaces for exploration, play, and experiential learning. Modern interpretations of this idea encourage designing child-friendly gardens that stimulate curiosity through edible plants, sensory paths, wildlife habitats, and interactive features—spaces where children learn ecological principles firsthand and naturally foster their sense of responsibility for the environment.

Jekyll emphasizes that gardening with children should promote active participation and observation. Rather than passive recreation, she encourages children to plant seeds, nurture plants, and harvest fruits, vegetables, or flowers. Modern gardeners and educators can adopt this method by creating hands-on opportunities—vegetable patches, pollinator gardens, or native plantings—that teach children the joy of growing their own food, as well as the cycles of nature and the value of patience and care.

Another key principle is the idea that gardens for children must be both safe and stimulating. Jekyll advocates the thoughtful arrangement of spaces, incorporating play-friendly materials and textures, comfortable and accessible garden beds, and diverse plant selections. Today’s ecological gardeners can translate this by using sustainable materials, low-maintenance native plants, and child-safe edible varieties, fostering safe exploration while also benefiting local wildlife.

Additionally, Jekyll highlights the importance of seasonal rhythms and sensory experiences in gardens designed for young minds. She encourages choosing plants with vibrant colors, pleasant fragrances, varied textures, and edible fruits that capture children's attention. Modern adaptations can include native wildflowers, aromatic herbs, brightly colored pollinator plants, and edible fruits and berries that engage all the senses, promoting emotional well-being and deepening children’s connection to their local ecosystems.

Finally, Children and Gardens stresses the lasting value of cultivating an early appreciation for nature’s beauty and diversity. Jekyll understood that childhood experiences with gardening could nurture lifelong stewardship and ecological mindfulness. Today, her vision aligns powerfully with contemporary goals of outdoor education, citizen science projects, and nature-based learning curriculums.

In short, Gertrude Jekyll’s classic work provides timeless guidance for creating gardens that spark wonder, promote learning, and inspire a sense of ecological responsibility in children. By applying these principles in modern gardens, families and educators can cultivate environments that enrich childhood experiences, foster ecological literacy, and plant seeds of stewardship that last a lifetime.

Published originally in 1914, Gardens for Small Country Houses by Gertrude Jekyll and Lawrence Weaver remains a cornerstone of thoughtful, harmonious garden design. Though written over a century ago, the foundational concepts presented are remarkably applicable today, especially for those pursuing landscapes that blend beauty, ecology, and practicality.

Jekyll and Weaver’s primary principle is the seamless integration of home and garden. Their vision emphasizes using landscape features, plant selections, and design elements that reflect the architectural character of the home. Today's gardeners can apply this principle by choosing cohesive materials and plantings that aesthetically extend their indoor living spaces outward, creating environments that feel unified and intentional.

The authors also address the challenges of sloped terrain, advocating the use of terraces to transform problematic inclines into opportunities for beauty and function. Modern practitioners find these insights invaluable when managing erosion, runoff, or limited gardening space. Through creative terracing, one can establish vibrant gardens, sustainable planting beds, and outdoor recreation areas even on challenging plots.

Jekyll and Weaver’s attention to architectural elements—such as walls, steps, stairways, and pergolas—is equally timeless. Their encouragement to include these structural features provides a lasting lesson for contemporary gardeners aiming to define spaces, guide movement, or establish visual interest in small gardens. Today, we might interpret this through modern hardscaping methods—using pathways, decorative fences, or sustainably sourced stonework—to create a sense of structure and permanence in garden spaces.

Additionally, the book celebrates the strategic use of climbing plants to soften built structures, a practice that has been enthusiastically adopted by modern ecological gardeners. Today’s adaptations include choosing native vines or incorporating edible climbers like grapevines, beans, or cucumbers. This simultaneously enhances biodiversity, provides food resources, and softens architectural features, echoing Jekyll and Weaver’s original aesthetic intent.

Remarkably, Gardens for Small Country Houses anticipates current trends toward compact, multifunctional landscapes. Even with limited space, the authors propose strategies for abundant, meaningful gardening. Modern practitioners translate this by utilizing vertical gardening, containerized plants, and edible landscaping—practices that maximize both beauty and productivity in small-scale gardens.

Lastly, though the book does not explicitly focus on native or edible plantings, it readily supports adaptation toward contemporary ecological concerns. By integrating native plants into garden designs, today’s readers can achieve ecological benefits such as improved pollinator habitats, reduced maintenance needs, and increased regional resilience. The original guidance of Jekyll and Weaver seamlessly accommodates these contemporary shifts, reflecting the versatility of their foundational principles.

In essence, Gertrude Jekyll and Lawrence Weaver's timeless insights continue to inspire gardeners to pursue harmony between home, garden, and ecology. For modern readers, Gardens for Small Country Houses is not merely a historical artifact but an enduring framework for thoughtful, beautiful, and sustainable landscape design.

"Roses for English Gardens" (1902)

"Lilies for English Gardens" (1903)

"Colour in the Flower Garden" (1908)

"Colour Schemes for the Flower Garden" (1919)